Q&A: Francisco Pelegri on his experience being genetics department chair

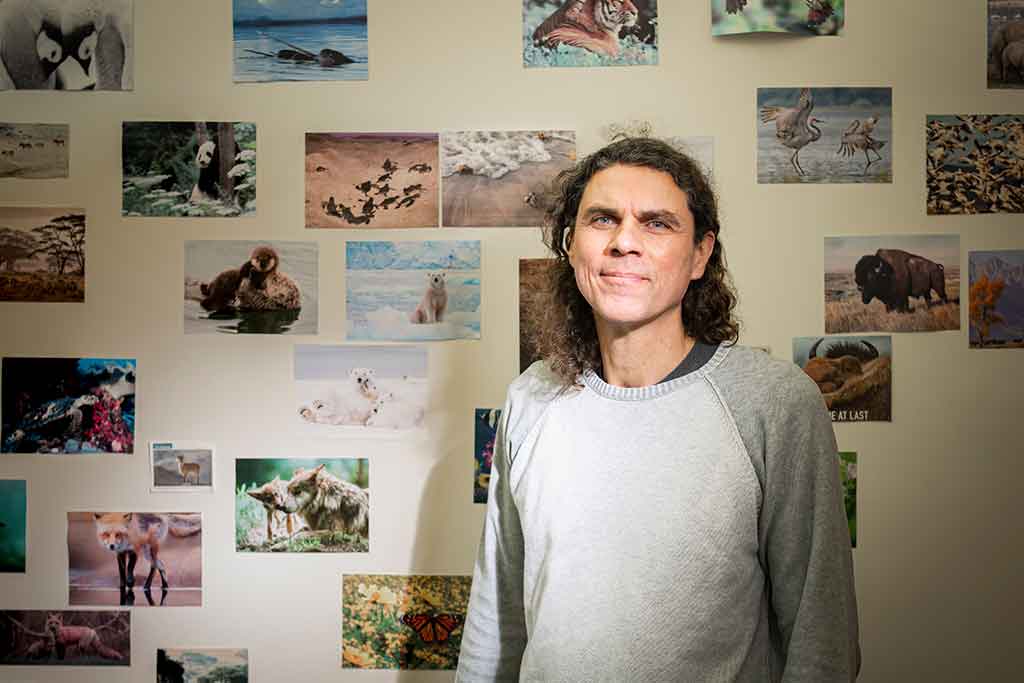

Francisco Pelegri, professor in the Department of Genetics, started serving as department chair in July 2020. His commitment to leadership, however, geared up a bit earlier than that – when he started heading up the department’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Pelegri, a developmental geneticist, studies how the vertebrate embryo develops, using the zebrafish as a model system. In recent years, he has been applying that knowledge towards biopreservation and reproductive approaches to preserve animal species.

In this Q&A, Pelegri shares some of his experiences and thoughts from being chair. This article is part of an ongoing series designed to shed light on the opportunities, challenges and satisfactions of serving in this leadership role.

Describe an experience that helped prepare you for being department chair.

I served in a number of committees in CALS, including the Curriculum Committee, the APC and a CALS restructuring task force. These activities helped me gain valuable experience to better understand the college, shared governance and academic leadership.

What has surprised you the most since becoming chair?

Perhaps how collaboration from multiple campus units can be leveraged towards valuable goals, from infrastructure to faculty recruitment and joint programs.

What are the biggest opportunities you see for UW–Madison in your area?

Genetics facilitates interdisciplinarity, and our campus is in an excellent position to make transformational advances such as promoting a lifestyle that is intrinsically healthy, developing increasingly effective strategies to treat disease, maximizing sustainable food and energy production, and preserving the natural world.

What are you doing to take advantage of these opportunities?

I work on campus-wide teams both for my own project on cellular methods towards reproduction and conservation, and to facilitate collaborations involving faculty in our department. These include necessary infrastructure and governance, grant opportunities and community-building.

What are the biggest challenges facing UW-Madison in your area?

A general challenge is to facilitate communication between various units to increase team-based research at a larger and more effective scale. More specifically with advances in genetics we’d like to better integrate data and models that translate genetic information to cellular and organismal function, which will allow greater predictive power and applied solutions.

What are you doing to tackle these challenges?

Our mission is multi-pronged, involving promoting relevant research and training the next generation of scientists, all in the context of societal benefit. As chair, I keep the Wisconsin Idea close to heart and strive to find ways in which research, teaching and service can synergize. For many members of our community, including students that are developing their career paths, this integration is an important motivation – after all the application of curiosity towards making a better world is one reason many of us have pursued science.

What is the most satisfying thing you have been able to accomplish as chair so far?

Simple things, like enhancing our common areas or organizing community-building events. Assisting junior faculty through the landscape and seeing their successes has also been a favorite activity.

How do you think your time serving as chair will impact the next stage of your career?

I anticipate that I’ll be an outgoing chair in the next year or year and a half, and I look forward to continuing my work developing scalable solutions to the biodiversity crisis. My time serving as chair has provided valuable team-building and operational expertise that will help me tackle what is undoubtedly a large, complex, multi-layered problem.

What is something about your department that you wish more people knew?

A little-known fact is that the Department of Genetics at UW–Madison was the academic home for Sarah Van Hoosen Jones as she pursued and obtained in 1921 a PhD in animal genetics from the University of Wisconsin – becoming among the first women in the United States to receive a doctoral degree focused on genetics.